Written for Operation Werewolf by Joshua Buckley

The French historian Fustel de Coulanges (1830–1889) is best known for his thesis that it was the religion of ancient Greece and Rome that led to the expansion and success—both culturally and militarily—of Classical civilization. This has little to do with the mythology of Mount Olympus, of Zeus and of Hermes, which is what we usually think of when we talk about the Greek belief system. According to Coulanges, what was important for the patrician families of Greece and Rome was the household-based folk-religion that honored the lineage and sanctified the family line (a more recent scholarly take on the Greek ancestor-cult—in case you want to read more about it—can be found in the work of Martin P. Nilsson). In Greek religion as described by Coulanges, there was an ongoing dialectical exchange that took place between the living and the dead. The ancestors continued to attend to their lineal descendants as guardian spirits, while the rites and veneration of the living served to—in some sense—bestow eternal life upon the departed. This made it absolutely essential that the family line was maintained, for “the dead had no future without living offspring.” This is no less true today, even if the traditional framework for understanding these things has broken down. In fact, there is probably no greater indictment of our society than its anti-natalism. A society without offspring is a society that is quite literally committing suicide. (A Lebanese friend shared an Arab proverb with me: “History is made by the people who show up.”) But while I am more than happy to see this society collapse into the dustbin of history, we are working to build something that will survive it. We should therefore keep in mind that building tribes—and not just Männerbünde—means establishing lineages.

With that being said, and while I think that having kids is important, my point in writing this essay is to take issue with men who use the fact that they have a family as an excuse for abandoning every project of self-overcoming. I’m willing to bet you have friends who fit this description. Before getting married and “settling down,” they were interesting, dynamic individuals. After the kids show up, everything changes. This is usually around the time that men get fat, stop working out, stop reading (with the exception, perhaps, of Good Night Moon), and stop spending time with their “old” friends—meaning guys who don’t have kids, or who haven’t let themselves be completely domesticated. When you visit them in their homes—which have been predictably relocated to commuter suburbia—you will notice the slow but steady replacement of every artifact of adulthood with plastic toys, indoor jungle gyms, and sippy cups. It’s as if the house now belongs to the children and the adults are just there to service their needs, like employees at a Chuck E. Cheese. Going on “vacation” now means visiting theme parks where other “adults” wear cartoon animal costumes—that is, if there are any vacations at all, because “Geez, kids are expensive!” At the gym where I practice martial arts, guys who used to train consistently will suddenly disappear for long stretches of time, offering only the lame-ass excuse that “Hey man, I have kids.” And?

There is no doubt that having children will change your perspective and priorities, and it should. Nature has hardwired us to love our children more than we love our friends, our parents, or even our romantic partners, and this makes perfect sense from an evolutionary standpoint. I feel an acute kind of revulsion for any man who would abandon his own children, and you can probably relate to this if you have kids of your own. One consequence of having children can be an increased emphasis on safety and security. Another is an attitude of self-abnegation that men will express when they say things like “I’ve sacrificed everything for my kids.” This is supposed to sound virtuous, and there is certainly an element of virtue in it, because once we have children, we are no longer free to be entirely selfish or self-absorbed. But is it really virtuous to sacrifice “everything” for your kids? It certainly sets up a vicious circle. Did my parents “sacrifice everything” for me, so that I could “sacrifice everything” for my kids? Am I “sacrificing everything” for my children so that they, in turn, will “sacrifice everything” for my grandchildren? This only makes sense if we apply to human beings the logic of a stockbreeder, whose only goal is to produce more animals.

For us, the goal should be to live lives that surpass the lives of our parents, and to have children that we can dream will one day surpass us. This is how our tribes will grow not just in numbers, but in power.

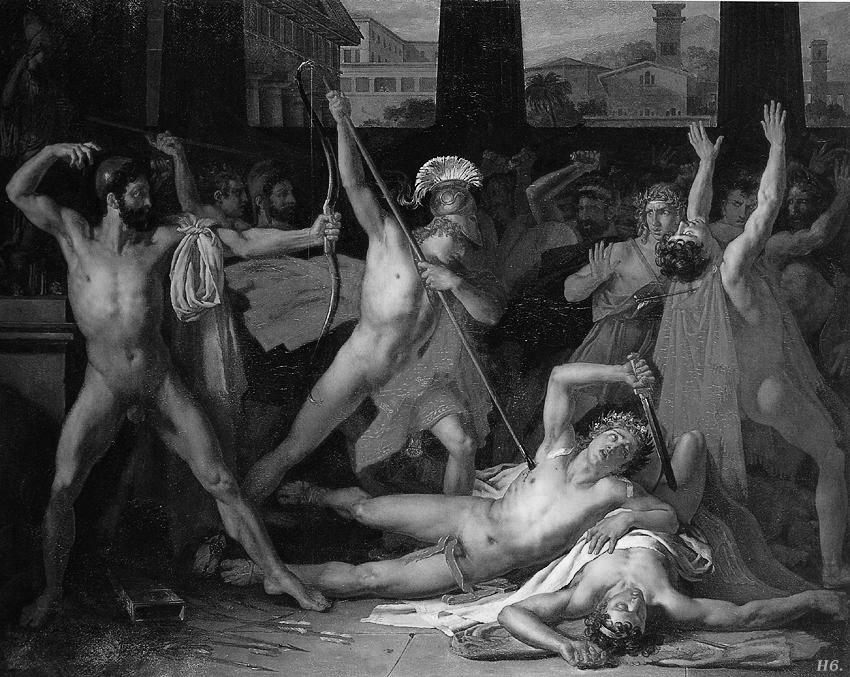

In the Old Testament, God “the Father” is presented as an angry, vengeful patriarch. He is jealous, insecure, and capricious. He is kind of a dick, actually, and as many other thoughtful people have pointed out, not really the kind of guy you would want for a dad. His son, Jesus, or at least Jesus as we meet him in the Gospel of Matthew, is somewhat more like a “modern” father, with all of that talk about “turning the other cheek” and not “judging.” Certainly, this is the Jesus of contemporary Protestantism (whether or not it has anything to do with the Biblical Jesus). Modern Jesus, like the modern father, is mostly just there to be a friend and comforter—part life-coach and part therapist. But as Alain de Benoist has pointed out, in paganism the gods do not have the same paternal character as the Christian God. They are neither abusive and judgmental “old school” fathers, nor are they sappy, sensitive “modern” dads. The gods of paganism are there to serve as exemplars and role models. This is why great heroes, through a process of historical and mythical transmutation, could actually become gods. The gods are there to inspire us and to provide us with the strength we need to become more than what we are. This is the destiny they have apportioned to us, although it is up to our own exercise of will to seize it.

This is also how I see our role as parents. Of course we need to be there for our children, to care for them, provide for them, and discipline them. This can, in and of itself, involve a considerable investment of time, money, and, in many cases, heartache. However, you are not doing your kids any favors when you give up on yourself in the process, whether or not you imagine that you’re doing it on their behalf. Odysseus might not have been the best father in the world—in The Odyssey, he leaves his son behind in Ithaca when he sets out on his adventures—but Telemachus could have done a whole lot worse than having a hero for a father. This is borne out at the end of the epic, when father and son are reunited, and Odysseus encounters his son as a grown man and an equal. Instead of settling into a life of bourgeois complacency, be a hero to your kids. Train more. Learn more. Struggle more. Develop yourself more, so that your children have something to aspire to. Then, when you die, you might have descendants who are worthy of tending the fires burning over your grave.